Our History

Fajr

6:01 AM

Zuhr

1:39 PM

Asr

5:58 PM

Magrib

8:09 PM

Ish’a

9:37 PM

Juma

01:30 PM

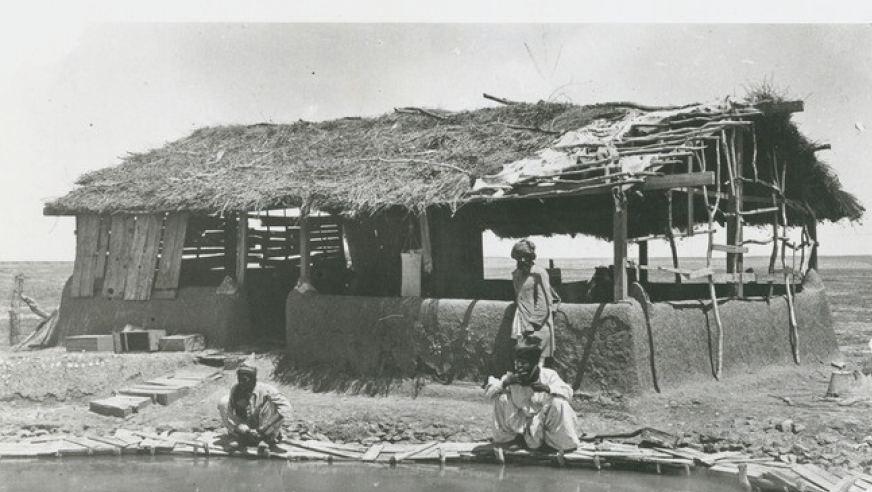

In January, 1866, the first group of 31 cameleers were brought from Karachi, India, to South Australia with 121 dromedary camels as a commercial arrangement by Thomas Elder, a colonial entrepreneur and pastoralist. Cameleers or “native handlers” and camels disembarked at Port Augusta and walked to Elder’s sheep property of Beltana station in the Flinders Ranges. “Cameleers” were originally collectively named as “Afghan”.

As the cameleers mainly originated from the British imperial colony of north-west India most “Afghan” cameleers were British subjects living in India, while a few were Afghan subjects of the “Ameer of Kabul”. The cameleers’ origins were of different tribal areas and included Baluchistan [now Pakistan], the Punjab, the Sindh province beyond the port of Karachi, Rajasthan, the North-West Frontier and Peshawar, Kandahar and Quetta in Afghanistan, Turkey and Persia [now Iran]. Many “sepoys’ based in Peshawar under Lord Roberts were unemployed in times of peace and looked for work elsewhere. Several arrived as camel handlers in South Australia in the 1880s.

The cameleers were predominantly Muslim [in earlier years referred to as “Mohammedan”] and some were Sikh.

The first Imam [originally referred to as a “mullah”] of the Adelaide City mosque, “Mullah Hadji Merbain”, 1886 – 1896, named their diverse tribes to be “Berohees, Mektanees, Sindhees, Kutohees, Borees, Hindus, and natives of Bombay, Calcutta and Punjab.” [1893]

Why they came to South Australia

As the arid Far North South Australia was developed from the 1850s on, copper, wool, grain and gold needed to be hauled to the coastal port of Port Augusta for export to Great Britain. Droughts, restricted water and feed and desert terrains reduced the reliability of traditional haulage beasts [bullocks, horses, donkeys]. In 1865 Thomas Elder, of Elder Smith Co. Ltd, owner of Beltana station and other northern pastoral leases, and investor in copper mines, sent an agent to explore camel markets in north-west India and Afghanistan to select breeds of riding and haulage dromedary camels to establish a haulage system in this state and beyond.

With the camels came “native handlers” or “Afghan” cameleers contracted in north-west India and Afghanistan. It was widely believed that they were best suited to manage the camels on the long ocean voyage from Karachi to South Australia and in transport work in the arid interior.

Why the mosque

By the later 1880s Faiz Mahomet, of Kandahar, Afghanistan was foreman [“jemidah”] of Elder’s Afghan and North Indian cameleers at Beltana in the 1880s and 1890s. He managed cameleers around Beltana, Hergott Springs [Marree] and Oodnadatta. He wanted unemployed, destitute, aging, transient and stranded cameleers to have a permanent religious, social and cultural centre that was a “home away from home”, where they could practice their diet, faith and customs.

Founding the mosque

The concept to construct a permanent mosque with courtyard in the Adelaide City commenced in 1886 when Faiz Mahomet invited the first Imam, Hadji Mullah Merbain of Coolgardie, Western Australia, to reside in Adelaide, in Little Gilbert Street. [Sands and McDougall Directories] In 1887, Faiz Mahomet applied for vacant Lots 22 – 28, Little Gilbert Street. In 1887 the Adelaide City Corporation approved plans for construction on those Lots.

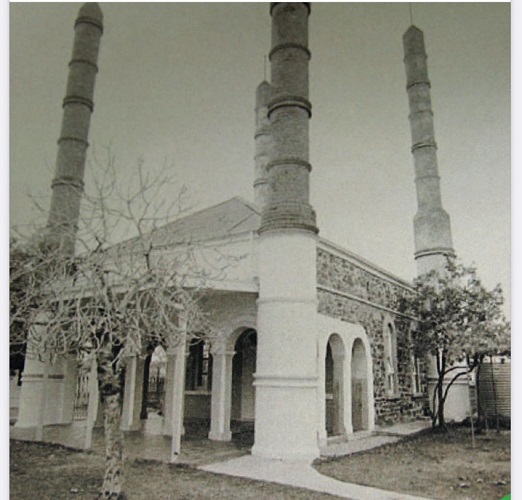

In 1888 – 89 the mosque was erected with blue stone, lime and whitewash. Later, red brick was used to build four pillars, four minarets and a high fence. When the grounds were opened in June, 1890, staff of the Adelaide City Corporation visited the mosque and courtyard, removing their shoes before entering it.

From 1890 the square “House of Prayer” [originally referred to by cameleers as “masjid”, July, 1890, and in English parlance as the “Afghan chapel”] measured 11.3 metres in length, 7.6 metres in width and about 5.5 metres in height. At first a low wooden fence was built on the boundary. Devotees entered the mosque from the eastern side [Logan Street] and crossed the large open courtyard.

Funding the mosque

The mosque cost 450 pounds to build with a limit of two years to complete payment.

From 1890 funds were raised by cameleers’ voluntary donations of an agreed amount. Camel drivers would pay 10 shillings a year, and camel owners or merchants one pound a year. [1893]

The budget remained in deficit because the first Iman directed funds to give charity to the destitute, infirmed and stranded cameleers. In September, 1893, Abdul Wade [or Wadi] from the Quetta district of Afghanistan, and a camel importer and cameleer employer based in Bourke, New South Wales, became the trustee when he paid 360 pounds to “preserve it from its creditors and keep it in the hands of his countrymen.” [ Advertiser, 1893]”

After 1897 limited funds afforded only “caretakers” to look after the mosque and its occupants.

The site of the first permanent mosque in South Australia in Little Gilbert Street was selected because the south-eastern corner of Adelaide had cheaper land taxes, it was close to the water table, to the North Terrace stock yards needed for sheep and cattle for community meals, close to the West Terrace Cemetery and to the main road leading to Port Adelaide.

The interior walls of the bluestone mosque were white washed [July, 1890]. The mosque featured a “mihrab” [1890] or alcove with a tiny round window, shaped as an acoustic niche in the western wall, so that devotees faced north-west to Mecca. It was where the Imam stood.

Interior lighting was supplied by a kerosene lamp suspended from the ceiling exterior lighting was supplied by torches attached to the exterior walls.

An area was designated for shoes which are removed before entering the mosque. As Cameleers were not permitted to bring their own women to South Australia there were no ladies to worship in the mosque.

The interior concrete floor was covered with strips of matting made by the cameleers [July, 1890]. Prayer mats, side by side, scarlet, blue, green and brown, were used by worshippers to kneel on when at prayer. Chairs were absent.

The Imam used the “minbar” or small set of steps to the side of the mihrab, to be visible and heard when he gave sermons on the “holy day”, Friday.

Small arched niches set in the interior white-washed walls held copies of the Koran, lamps [July, 1890] and a glass vase with 2 drooping peacock feathers. Over time the white wash cracked on the inner mosque walls so today protective timber laminate lines the interior walls and ceiling.

On the interior walls were glassed windows and framed pictures giving views of Mecca and sacred cities including the Prophet’s tomb.

Tessalated tiles of various shapes, size and colour paved the porch floor. The porch was enclosed with numerous graceful arched columns protected by wrought iron tracery. [1891]

Four stately red brick pillars were added on each corner of the building.

By July,1890, in the eastern courtyard a large excavation was bricked up and cemented, with a step down, in front of the cloister to prepare for the ablutions pool. It was about 15 feet long and 18 feet wide. Cameleers stepped down into the pond to wash themselves before entering the mosque. In the pool were 350 fish – gold, silver and red [1903]. In the centre was a fountain from which a thin jet of water rose into the air then fell into the wide basin. By 1935 the pool was empty and dry. After 1935 a cement washroom for ablutions was built on the north side of the yard. By 1951 the pool was filled in and the area cemented over.

A large open area [originally referred to as the “temple courtyard”] was on the northern and southern sides, then the eastern side.

The mosque was accompanied by garden beds laid between the borders of the pool and the eastern fence line of the mosque. They were filled with flowers of different colours which ”grew lush and mature” [1903]. Some evergreen and fruit trees, including an old fig tree, were planted around the edges of the courtyard. Vines clung along the fence and around the cottages.

“Cottages” or courtyard buildings included a cottage for the first Imam, his wife and two children [1890 – 1896]. Two adjacent sleeping rooms or “cottages”, stretchers under the trees and shared tenements in Little Gilbert Street provided shelter to destitute, unemployed or stranded cameleer drivers, labourers and hawkers. There was a kitchen, a woodshed and a room in which Indian mat making was carried out [1903]. A library was added.

The original wooden fencing was replaced in the 1890s by higher, red brick walls and a wooden lattice gateway that enclosed the mosque and its grounds. At one stage the red brick fence was whitewashed, white being one of the Prophet’s favourite colours symbolising purity, then later the fence wall was restored to its red brick colour.

At one stage the wooden gates were painted green, from 1935 to 2005, then repainted brown.

The cameleers added cone, pyramidal shaped structures over the gateway and along the top of the red brick wall.

Minarets

The construction of four red brick minarets commenced in 1901. In August, 1901, a newspaper advert asked for “a number of good scaffold ropes. Apply at Afghan mosque, Little Gilbert Street.” All four were completed by 1903.

The minarets are distinctive, cylindrical, slender constructions of about 40 feet high. Their diameter is about three feet at the base and gradually diminishes in girth as they rise.

Two minarets cost 150 pounds to build, and the other two were an additional 100 pounds. [1903]

By 1903 each minaret was crowned with a staff with a gold globe, perhaps representing the full moon.

In 1903 the two front minarets were white washed. The two rear minarets remained in red brick. In 1945 all four minarets were white washed.

To maintain the mosque the Adelaide City Council in 2010 funded the restoration of a minaret and a pillar that had partially collapsed.

The Adelaide City mosque was made by skilled “Afghan” cameleers to meet their countrymen’s spiritual and welfare needs when they visited and rested at the mosque as a “home away from home”. It is a key landmark of the community and contribution of the Afghan cameleers who lived, worked and raised families in South Australia, 1860s – 1920s.

This mosque is the only mosque in the city of Adelaide’s square mile. It was the first mosque to be built in an Australia city.

The Adelaide City mosque is nationally significant as being unique to Australia’s Islamic architecture [2016[. It is nationally one of the very few original, authentic, permanent relics of Afghan cameleer settlement in Australia. Being conceived of in 1886, built in 1887-88 and opened in 1890, it is the oldest permanent mosque, and longest continually active mosque in its original state, in Australia.

In July, 1980, the Adelaide City mosque was listed by the Adelaide City Council as a State Heritage Place in the SA Heritage Register. It is a significant and unique feature of the heritage character of south-west Adelaide.

A n additional heritage contribution is the “Afghan section” in the West Terrace Cemetery. In 1896 Faiz Mahomet procured a land allotment at that cemetery in which cameleers could be buried according to their customs.

Cameleers travelled to the Adelaide City mosque from as far as Marree and Oodnadatta, South Australia, Broken Hill in New South Wales and Coolgardie and Kalgoorlie in Western Australia to gather with countrymen at least once a year for the Islamic [1890] celebration of Ramadan [referred to now as “Eid”]. In 1890 80 “Afghans” attended the Ramadan festival. In 1903 25 to 30 were long distance visitors. [Advertiser, May, 1903, pg. 5]

The Adelaide mosque’s Imam travelled to northern outback Marree and Oodnadatta cameleers and families who could not travel to the city mosque.

The Adelaide mosque has functioned continually as a “multicultural”, cosmopolitan centre. Cameleers originated by the 1880s from Afghanistan, north-west India, Turkey and Iran. Some were Sikhs. Today it functions with a other nationalities. Prayers are in Arabic but all community services are spoken in English.

After 1890 unemployed outback cameleers, mainly Muslim, travelled to Adelaide to seek support at the mosque. Being in a metropolitan area the cameleers took up “other occupations as hawkers, labourers and herbalists.” [1893].

Afghan or Indian Muslim herbalists were named “hakims”, an Arabic term used across the Arabic world. The occupation of herbalism in Afghanistan and northern India was taught from father to son over centuries. Hakims practiced as oculist and piles specialists. eg “Hakeem Mahomed Bakhsh”, “Hakim Ghulam Deen Mahomed”.

The hakims imported dry [powder, pods, seeds] herbal ingredients from India and Afghanistan, eg turmeric, dried figs and dates, senna leaves and pods, and wormwood, which they compounded with local fresh ingredients, eg butter, honey, beetroot leaves, vegetable stems, rose petals and goat’s milk.

As south-west Adelaide small cottages were without back gardens herbalists depended on procuring fresh ingredients from the Adelaide Central Market, opened in 1846, in Gouger Street.

In the early 1900s, and in the 1920s, “Afghan” herbalists rented first floor rooms for consultation and treatment in Gouger Street, eg at numbers 33, 39, 59, 107 – 109, and 201. These rooms were between the Central Market and the city mosque.

The most famous ex-cameleer and herbalist Afghan Mahomet Allum, after 40 years as a cameleer, procurred an 8 room, two-storey house at 181 Sturt Street in south-west Adelaide. From 1928 to 1953 it was his home, consulting and preparation residence. His own vegetable garden was nick-named “Orchard of Asia”. He treated 500- 600 people a day. Every three years he travelled to India and Afghanistan to procur more ingredients. He was at the Central Market every week and spent every Wednesday at the Adelaide mosque.

From 1954 he was a herbalist on Anzac Highway until his death in 1964.

The Adelaide City mosque, with the “Afghan section” in the West Terrace Cemetery, brought the “east to the west” [1930], thus contributing to the heritage character of south-west Adelaide.

The Adelaide City mosque was supported from 1890 by voluntary contributions. Some camel owners who donated additional service and money to the upkeep of the mosque included Sheik Abdul Kader of Marree in the 1920s, Goolam Rassoul of Afghanistan (1913 – 1941), Izze Khan in the 1940s, and Bejah Dervish of Marree and Gool Mahomet of Farina until 1950. Gool Mahomet travelled to Adelaide from Farina several times to attend upkeeping of the mosque. Voluntary contributions of funding to support the mosque and its ongoing development continue and are ongoing.

Contributions of community support and services by the mosque are ongoing. People have come to the mosque since the 1890s for refuge, assistance, and personal, legal and travel advice. It is a centre of community wellbeing. It offers counselling services, access to palliative care, and mental well being. It offers the mosque’s community a “sense of belonging”.

This mosque contributes a prayer centre and services to an increasing, diverse immigrant multicultural community. After the last of the cameleers attended the mosque the mosque took on a new lease of life with post-World War Two Muslim migration and has since been thriving. After 1950 different countries of Muslim migrants include Bosnia, “Yugoslavia”, Lebanon, Pakistan, Algeria, Indonesia, Malaysia and Africa, have attended here [2019]. The Adelaide City mosque continues to be used by a cosmopolitan congregation.

As the size of the congregation of the Adelaide City mosque has continued to increase, additional spaces for devotions and community services have been created. The porch area of the mosque and original arches were enclosed to extend the formal prayer area. The whole courtyard on the eastern, northern and southern sides is cemented over and covered by curved glass ceilings to expand and shelter the praying area. A balcony was added in the main building to provide a place for Muslim wives and daughters to pray. A sound system was installed to make the Imam’s leading in prayer and sermons audible to the whole congregation. Consideration is being given to add on more land for the site to cope with the increasing congregation.